May 30, 2002

UW Tacoma prof creates aquarium exhibit

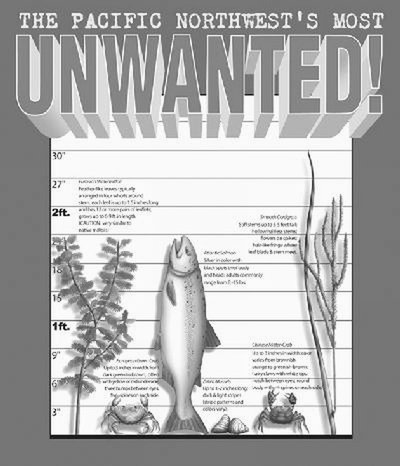

If you can create an aquarium exhibit that fascinates and entertains kids and their parents with green crabs, tiny zebra mussels and the cute Chinese mitten crab, along with vibrant graphics and stories that warn of alien invaders, then education sneaks into a fun adventure.

That’s just what a UW Tacoma professor had in mind for the “Alien Invaders” exhibit at the Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium. The recently opened exhibit is part of the aquarium’s regular displays within the new Marine Discovery Center, but the professor and his co-creators plan to develop a similar, larger traveling exhibit that will educate and inform across the nation.

The “Alien Invaders” exhibit was developed primarily by David Secord, UW Tacoma environmental science professor; John Rupp, the Point Defiance curator of marine animals, and Kristin Hemmelgarn, a former undergraduate UW Tacoma student turned part-time “Alien Invader” employee. More than a dozen other UW Tacoma undergraduate students have also contributed to the project during the last four years. Their efforts were supported by a host of local and federal agencies and environmental organizations.

“Aquariums and zoos are an untapped resource for public education on biodiversity. Because they are all about combining entertainment, education and conservation, they are perfect for this kind of outreach,” says Secord. “More people visit zoos and aquariums annually in the U.S. than attend all professional sporting events combined, so this is a great way to educate the public about aquatic invasive species.”

He points out that this problem, according to one university study, cost more than $137 billion annually in the U.S. alone.

In fact, invasive species — a.k.a. alien invaders — are the second leading contributor to endangered species. Habitat degradation is enemy No. 1. Third is over-harvesting. Fourth is pollution.

“Decline in biodiversity is connected to quality of life in all kinds of ways that are well documented,” says Secord. “People are involved in the spread of invasive species and we can reach people, which means we can prevent and control new invasions. We can stem the tide. We want to place an emphasis on prevention, and education is at the heart of making that happen.”

All that bad press may make you think the Chinese mitten crab or the prolific zebra mussel are evil incarnate, but that’s not the case.

“The aliens aren’t really bad themselves. They are bad when they are out of place, because they can take over for native species and even drive them to extinction,” says Hemmelgarn.

For example, the striped-shelled zebra mussel, on average, is the length of a human fingernail, but in the United States, these mussels multiply rapidly and, in addition to threatening native species, establish such large populations they clog pipes in drainage systems. They have done tremendous damage in the Great Lakes, where the invasion started from ships’ ballast water, and have spread throughout the Mississippi River basin, where they are threatening dozens of native species. They are now in the Missouri River, which could take them into Montana. An international initiative is focused on preventing zebra mussels from crossing West over the 100th meridian.

“If they reach Montana, all you have to do is move a boat from there to a Washington lake or river and zap, you’ve got a problem here. That’s one of the reasons for this exhibit,” says Secord.

Plants can be aliens, too. Spartina grass, commonly known as smooth cordgrass, has been taking over mudflats in Willapa Bay for years, altering habitat for shorebirds, shellfish and fish. Other aliens may carry parasites. For example, the Chinese mitten crab is a suspected host of the Oriental lung fluke that causes disease in humans. The crab itself is wreaking havoc in San Francisco Bay, where juvenile crabs burrow into banks, causing erosion and disrupting efforts to enhance native endangered fish populations. Atlantic farmed salmon accidentally released into Pacific coastal fisheries are also aliens because they may compete with native endangered salmon.

Although many alien invaders arrive in local waters through ships’ ballast water, individual human behavior — such as dumping a home aquarium or engaging in certain fishing and boating practices — can contribute. Not all alien species survive, and not all that survive will thrive to the point of endangering native species, but every species has the potential to cause unexpected economic, ecological or public health problems when moved to a new environment beyond where it evolved.

Because of the human factor, public education is critical.

Secord says growing awareness created by this exhibit and others like it will also generate support for public policy changes. He has been active in supporting legislation to help protect the state’s shorelines from invasive species. The state Legislature has already passed legislation addressing aquatic invasive species. Other states and the federal government have been active as well.

Secord and Rupp are pleased the development of the exhibit involved research and other contributions by so many undergraduate students.

“Whatever it is our students work on will have vast downstream impacts. Not just on awareness, but on future invasive species policy,” says Secord.

More than a dozen UW Tacoma undergraduates have been directly involved in all aspects of combining cool critters with public education in creating the exhibit, including developing the text and artwork, doing scientific background research and learning about animal husbandry to see how to keep things alive on exhibit. Some continued the work after graduation.

Hemmelgarn has become an alien expert, beginning her work on the project while earning a bachelor of arts degree in environmental studies and continuing as a part-time employee on the project after she graduated in June 2001. In working with One Plus Two Inc., a design firm that specializes in scientific exhibits, she helped translate science into something the general public would understand and appreciate.

“It had to be simple, eye-opening and accurate,” she says.

Her work has involved publishing an article as lead author with supporting roles by Rupp and Secord in a national publication about invasive aquatic species.

“None of this would have happened without Kristin. Because of her work, the exhibit allows us to bring a wealth of knowledge and information about aquatic invasive species together and hit a vast cross-section of the interested public,” says Secord. “John Rupp and I first conceived of the exhibit in 1998, but we are both overwhelmed with our regular workload. Kristin’s efforts, creativity and intelligence filled in the gaps and kept this thing moving.”

The exhibit viewed today is a 500-square-foot installation. Its creators plan to develop a 2,000- to 3,000-square-foot version that will travel to zoos, aquariums and scientific museums across the country.

“The science and the environmental messages are similar everywhere. The species highlighted should change depending on the geographic location,” says Hemmelgarn.

Secord and Rupp are confident “Alien Invaders” will attract further financial support from sources like the National Science Foundation to allow for expansion and touring.

The exhibit was made possible with support from the National Sea Grant Program, which is part of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as well as the Washington and Oregon Sea Grant Programs, Pacific Northwest Marine Invasive Species Team, Puget Sound Action Team, Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board.

The small prototype exhibit is locate