April 18, 2002

UW students to send mice to space

Students from the University of Washington have won a place on a team that plans to launch mice into space, seeking answers to the little-explored question of how Martian gravity affects mammals.

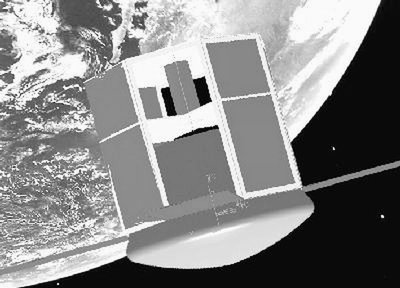

The UW aeronautics and astronautics students will work with fellow students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Queensland in Australia to build the Translife Mars Gravity Biosatellite, a spacecraft capable of carrying the mice in orbit for nearly two months under simulated Martian gravity, then landing them safely back on Earth. The mission will feature several firsts, including the first birth of mammals in space.

The Mars Society, a private organization that promotes the exploration and settlement of Mars, officially announced the team today, after having hosted a competition to determine the best concept for a spacecraft to undertake the endeavor

The UW contingent will build the biosatellite’s carrier module, which will provide the power, propulsion, navigation, artificial gravity and other elements necessary to sustain the entire spacecraft during the mission. MIT and Queensland will be responsible for the re-entry module, which will house the mice.

“From a student perspective, this sort of project is priceless,” said Adam Bruckner, chairman of the UW Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. The UW team worked for three months in a senior-level space systems design course under the direction of lecturer Bogdan Udrea to come up with a winning design. “It’s one thing to learn about spacecraft from a book, but it’s a completely different experience to design and build something that will actually go into space.”

It’s not the first such undertaking for the department, Bruckner added.

“Our students have had previous experience with the Dawgstar project,” a small self-propelled nanosatellite scheduled to be launched from the Space Shuttle next year, he said.

The Translife Mission will seek answers to a critical question involving the human exploration of Mars: can people live, function and develop normally in Martian gravity? Mars’ gravity is three-eighths that of Earth’s, and scientists don’t know whether that is sufficient to avoid serious health effects, such as bone loss and muscle deterioration, that astronauts have encountered while living in the weightless environments of space stations.

The Mars Gravity Biosatellite’s crew will boldly go where no mice have gone before: during the 50-day flight, some crewmembers will give birth — the first mammalian births in space. The offspring will develop in simulated Martian gravity for the duration of the mission. At the end of the flight, the spacecraft will re-enter the atmosphere and return the mice safely to Earth for further study.

Other mission firsts include: The first private launch and recovery of a spacecraft carrying mammals, the first launch and recovery by students of a satellite, and the first study of living organisms in a partial-gravity environment.

While circling the Earth, the spacecraft’s carrier module will spin, using centrifugal force to simulate gravity on Mars. The carrier module must also establish and maintain a precise orbit, provide power and support to sustain the mouse habitat and communicate with mission control, all complex challenges that the UW students are addressing.

Project participants are evaluating options for a launch vehicle. Students are also seeking both private and public funding to finance the cost of the mission, which, with trials and testing, could total as much as $10 million. An anonymous donor has pledged to match contributions at 50 percent.

For more information about the project, check the Web at www.marsgravity.org/.