January 7, 2002

If it’s winter, the Skokomish River must be flooding

With a constancy that would impress the swallows at San Juan Capistrano, the Skokomish River seems to flood each year at the first sign of Western Washington’s rainy season.

Recent research at the University of Washington has found that a series of land-use decisions dating from the 1930s, from road building and streamside logging to dam construction, led to sedimentation that has made the Skokomish perhaps the most flood-prone river in the state.

“It’s always on the leading edge, the first one to flood, and it floods several times,” said David Montgomery, a UW professor of earth and space sciences. “Typically a river will flood about once a year. But the Skokomish floods two, three, four, five, six times a year.”

Research published by Montgomery and S. Chereé Stover in the Journal of Hydrology shows that the amount of water carried by the Skokomish hasn’t changed appreciably, but the river’s main channel has gotten 5 to 6 feet shallower since the early 1960s because of sedimentation. Stover conducted the research for her master’s degree. She since has received her doctorate from the University of Colorado and now is with the petroleum company BP.

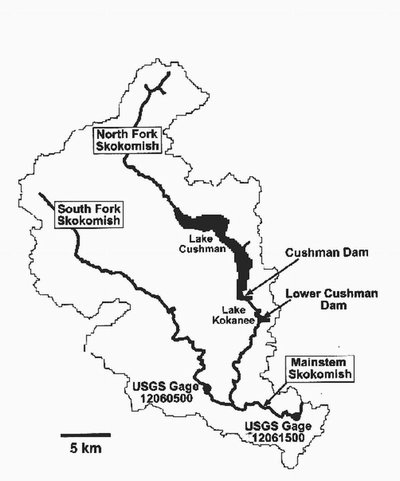

For her master’s degree, Stover examined records from two river-level gauges to determine how the river’s capacity to hold water has changed since 1926. That’s when the Cushman Dam was built on the north fork to supply power for Tacoma City Light. The Lower Cushman Dam was added four years later.

One gauge is above the confluence of the north and south forks, in Mason County just northwest of Shelton, and the other is in the floodplain, between the confluence and where the river empties into Hood Canal near Union. The gauges, maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey, measure how high the water is and its depth to determine the water flow rate. Those figures can be analyzed to show how the height of the riverbed has changed over time. What became clear, Montgomery said, was that the amount of water being carried by the Skokomish in recent decades hasn’t changed appreciably, even though flooding has become much more common.

The constant flooding has affected the Skokomish Indian Reservation, which lies below the confluence of the north and south forks, and people who live or farm in the river’s floodplain.

Records indicate the riverbed rose and fell in normal cycles into the late 1940s or early 1950s. That probably occurred in part because capacity was maintained by human interventions, including gravel mining in the river from 1932 to 1934 for the construction of U.S. 101 nearby, and work to clear logging debris from the channel in the early 1940s.

However, erosion from areas adjacent to the Skokomish headwaters in the Olympic Mountains began to deposit sediment in the riverbed, Montgomery said. It is not clear that timber harvesting and road building in that area had an immediate impact, he said, but they would at least have contributed to sediment buildup during 25 years.

The situation was aggravated because, with the two dams blocking the north fork, there no longer was sufficient water volume to scour sediment from the channel, Montgomery said. As the channel filled in, it became less and less capable of handling its normal flow and so the river often spilled its banks.

“You turned the water off and you turned the sediment up,” Montgomery said.

In addition, erosion control measures such as riprap (stones used to reinforce the bank) prevent the river from spreading out in some places, making flooding worse in other areas.

As the Skokomish flooding became more common, Montgomery suspected the historic records would provide some clues.

“When Chereé was looking for a project for her master’s thesis, I suggested that she do this to see if there was a simple reason behind the flooding,” he said. “It turns out there is.”

###

For more information, contact Montgomery at 206-685-2560 or dave@geology.washington.edu; or Stover at (281) 366-5402 or stovers@bp.com