For two billion people across the planet, these symptoms are part of daily life.

They’re part of sitting in class, trying to learn. They’re part of going to work, trying to provide. They’re part of living with soil-transmitted helminths (STH) — more commonly known as intestinal worms — inhabiting victims’ bellies, sapping their nutrients, and stunting their physical and cognitive development.

In countries where the disease is prevalent, soil-transmitted helminths have long been a public health problem and a human rights issue — and the UW School of Public Health is doing something about it. Researchers are playing a leading role in DeWorm3, a project coordinated by the Natural History Museum in London and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. DeWorm3 is providing the platform for one of the largest implementation science projects in the field to date. Its core mission? To interrupt the transmission of intestinal worms.

It’s here in the Department of Global Health, in partnership with the School of Medicine, that the first-ever Ph.D. program in metrics and implementation science is transforming the way people approach population health to improve lives. Implementation science is also key to the UW’s Population Health Initiative, launched in 2016 with the goal of improving human health, environmental resilience and social and economic equity around the world.

Implementation science works to equally value voices on the ground, giving as much weight to feedback from community members as it does to local health officials and funders. – Arianna Means

MEET DR. PETER CHERUTICH, '06, '15

Learn how the School of Public Health's first implementation science Ph.D. graduate put his education to work to avert 5,000 new HIV infections through pro-condom advertisements and large-scale male circumcision campaigns in his home country of Kenya.

In 2013, Dr. Peter Cherutich, ’06, ’15, — the first graduate of the world’s first Ph.D. program in implementation science — took on a contentious issue. As the deputy director of medical services in Kenya’s Ministry of Health and former head of its National AIDS and STI Control Program, he and his team pushed out an informative — and controversial — advertisement promoting condom use among married couples who were having affairs.

In Dr. Cherutich’s home country of Kenya, that’s about 30 percent of the married population, most of whom don’t use condoms. In Kenya, 6 percent of adults are HIV positive. Religious leaders called for the ad’s removal, claiming it promoted extramarital affairs, but Dr. Cherutich knew something had to change. Through awareness efforts, large-scale male circumcision campaigns, and testing and care, he pursued one goal: HIV prevention. His work tripled population coverage in just three years, leading to an estimated 5,000 new HIV infections averted.

“Implementation science through research and rigorous political advocacy laid the foundation for a successful implementation of male circumcision by removing social and political opposition to the scale up,” says Dr. Cherutich. “Noting how many HIV infections have been avoided through male circumcision is very gratifying.”

Implementation science is research-based and scientific, but it’s also action-oriented. It’s actually taking that next step, bridging the ‘know-do’ gap. – Arianna Means

Means, a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Public Health and former Gates Foundation research analyst, came to the UW to earn her master’s in epidemiology after serving in the Peace Corps. As a Peace Corps volunteer, she was stationed in rural Zambia, working on community-led malaria prevention campaigns and HIV testing and treatments. “There’s no substitute for that level of real world experience,” says the Atlanta native. “It’s one thing to study diseases related to poverty, but it’s another to live with people who have been subject to it for years.”

Intestinal worms and poverty: An ongoing cycle

And it’s another thing altogether to solve issues surrounding disease and poverty — two public health, human rights issues that often pose a chicken-and-egg problem: in the case of soil-transmitted helminths, poverty gives rise to worms; worms reinforce poverty.

These worms are all over the world, but in countries like Japan and the United States, public health officials have been able to control or even disrupt the transmission of the disease as the nations develop economically. In impoverished areas of Africa and Asia, they're still battling the cycle. So what are the barriers to eradicating this malady on a global scale?

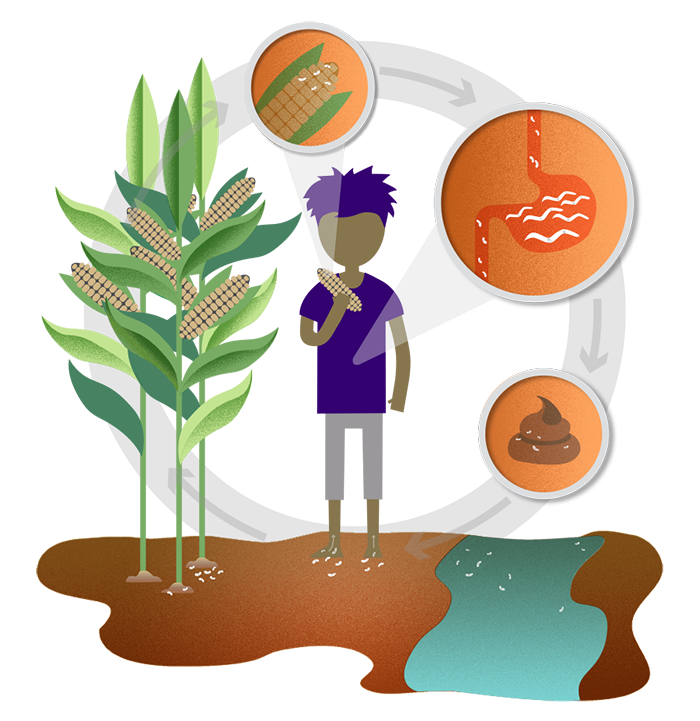

THE LIFE CYCLE OF INTESTINAL WORMS

- Eggs attach to fruits and vegetables, which often go unwashed before they're eaten (whipworm and roundworm)

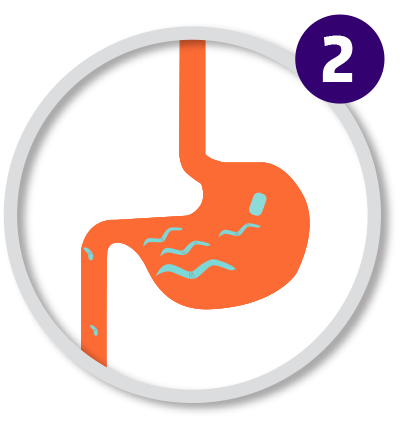

- Eggs and larvae make their way to the gut, where they sap nutrients and grow

- Worms produce eggs, which are passed in feces

- People often defecate outside, contaminating soil and drinking water

- Larvae penetrate bare feet and enter the gut through the bloodstream (hookworm)

- Crops are fertilized by feces which often contain eggs

The primary culprits are limited access to clean water and sanitation resources, and the fact that in current deworming programs, only preschool- and school-aged children are receiving treatment, says Means.

The current deworming treatment

A pill called albendazole is administered to preschool- and school-aged children once or twice a year

The pill sterilizes eggs, larvae and full-grown worms living in the child's gut and sapping their nutrients

The worms pass through feces. The child is rid of the infection, but is at risk of being re-infected through contaminated water or untreated adults

Worm infections come from eating unwashed fruits and vegetables that have a trace of fecal matter. They come from drinking contaminated water, or from simply walking barefoot — some worms migrate through the skin. Because only children are being treated, a child could be rid of his or her infection one day, then go back to their earthen-floor home and get re-infected the next. “Unless you can get this really intense community-wide treatment going, disrupting the transmission is pretty challenging,” says Means.

And therein lies the solution to break the cycle: programs that treat everyone, in all households, more than once a year.

We’re trying to see what happens if we actually treat the entire community — preschool-aged children to adults — and compare that to the current standard of only treating kids. – Arianna Means

Implementation science at work

Mass drug administration programs have targeted entire communities before, and the strategy works. A large-scale effort to squash another parasitic disease, lymphatic filariasis (commonly known as elephantiasis), kicked off in 2000. Community-wide treatment helped transmission rates drop 43 percent in just 15 years. More than 800 million people have been treated so far, and in some countries, the transmission cycle has been interrupted. By 2020, the hope is for lymphatic filariasis to be eliminated completely.

There's an opportunity here, says Means, to leverage the existing treatment platforms already in place in Benin, Malawi and India for DeWorm3’s efforts. In fact, both lymphatic filariasis and intestinal worm treatments co-share a drug: albendazole.

This is what implementation science is all about.

-

Arianna Means

Research Scientist / DeWorm3

Former Research Analyst / Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Peace Corps Alum

Bachelor of Arts in International Relations and Community Health, Tufts University, ‘09

Master of Public Health in Epidemiology, University of Washington, ‘13

Ph.D. in Global Health: Metrics and Implementation Science, University of Washington, ‘17

-

Kenny Sherr

Co-Director / Global Health: Metrics and Implementation Science

Director / Mozambique Programs, Health Alliance International

Associate Professor / Global Health

Adjunct Associate Professor / Epidemiology

Adjunct Associate Professor / Industrial & Systems Engineering

-

Judd Walson

Principal Investigator / DeWorm3

Director / Strategic Analysis, Research & Training Center (START)

Associate Professor / Global Health

Associate Professor / Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Associate Professor / Pediatrics

Adjunct Associate Professor / Epidemiology

Judd Walson

Principal Investigator / DeWorm3DeWorm3 goals: Learn more about the three main objectives of DeWorm3, and the importance of working with the World Health Organization and Ministries of Health

Starting in 2017, at the end of the lymphatic filariasis programs in these countries, DeWorm3 will randomly assign communities to either maintain the standard program of only treating preschool- and school-aged children for intestinal worms, or go to a highly intensive treatment plan where they treat everyone in the community twice per year. And they will conduct further implementation science research activities along the way to understand best practices in intervention delivery and opportunities to maximize community participation. In 2020, both types of communities will stop all treatment. Two years later, DeWorm3 will compare the groups and determine whether the intensified treatment program was more successful. If so, they’ll work with policymakers to develop relevant guidelines that could be used to bring the intensified intervention to scale.

Collaboration is the key to it all, says Means, who plans to continue working with DeWorm3 after earning her Ph.D. from the School of Public Health this year. “In each country, there’s a really passionate and amazing group of partners who are helping implement this work. It’s really rewarding to be sitting in a room full of people from all over the world who are all working toward the same goal.”

The potential impact of DeWorm3’s work for an infection-free world is unparalleled, says Means. “For a parent, just knowing your kid isn’t at risk of contracting an infection is huge,” she says. “There’s peace of mind in knowing your child can run around barefoot without getting a belly full of worms.”

Health is a human right. The UW and the School of Public Health are working toward equity, and I think that’s pretty unique to the culture here. – Arianna Means

Originally published February 2017