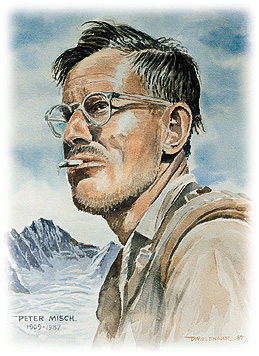

Peter Misch Peter Misch

The Office of the Department of Geological Sciences has framed a watercolor

portrait of Professor Peter Misch, surrounded by reproductions of a selection

of his alpine landscapes, which represent a childhood interest that preceded

his development into a world renowned geologist and teacher.

As a mountaineer and skier, and artist, Misch was somewhat of an anachronism

during his 40 years within the department; he believed strongly that understanding

"the language of the rocks" required heading into the high hills

with rock hammer, climbing gear, and two weeks of groceries. It was through

his zestful rock-seeking scrambles through the Alps, Pyrenees and Karkoram

Himalayas--along with close camaraderie with like-minded, mountain-loving

students--that he attracted so many to seek him out as their theses adviser.

During his tenure, Peter (as his grad students came to know him) supervised

the M.S. and Ph.D. thesis projects of more than 125 students, with study

areas that ranged among the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, Canada,

Alaska, eastern Nevada, Great Britain, Africa, the Arctic and Antarctica.

Born in Berlin in 1909, Hans Peter Misch started doing many things early

in life--painting watercolors at 5, skiing at 6, collecting fossils at an

outlying farm at 10, and taking up serious mountaineering at 14. As a "wunderkind"

geologist, Peter received his doctorate at age 23 from Gottingen University,

with his thesis that covered the geologic structures and petrology of the

central Pyrenees in northern Spain. Because of his strong combined activities

in geology and mountaineering, Peter was invited to join the scientific

contingent of the 1934 German Nanga Parbat Expedition to the Karakoram Himalayas.

It was through these wide travels among the world's high mountains that

Peter had become an avid supporter of the controversial theory of granitization,

whereby--rather than occurring principally as an intrusive igneous rock--granite

is found in the core of most ranges as the end-product of a metamorphic

cycle that changes mud-to-shale-to-slate-to-phyllite-to-schist-to gneiss

and finally to granite.

By 1936, Hitler's persecution of anyone of Jewish ancestry had Peter

with his wife and baby daughter Hanna leaving Germany for China, where during

WW II he taught at Sun Yat Sen University in Canton before the Japanese

invasion of Manchuria forced his move to Peking University in Yunnan. But

his wife became ill and with Hanna returned to Germany, where she died during

the Holocaust. Peter was not reunited with Hanna until at age 16 she came

from Germany to Seattle.

After the war, Peter had come from China to California, where he taught

briefly at Stanford and met and married the vivacious and equally talented

Nicoletta ("Niki") Rosenthal. After Peter was lured to the UW

in 1947, Niki became his helpmate as they found their home among geologists,

students, mountaineers and skiers of Seattle, while raising their sons Felix

and Tony. And among Peter's greatest joys in the post-war years in Seattle

was to regain contact with some of his Chinese students, some of whom had

survived the Cultural Revolution and attained respected positions in the

scientific community of China.

Despite a rapid-fire, German-accented delivery in the classroom, Peter's

daily lessons were enhanced by his illustrative talent. By the end of each

daily session his blackboard was covered from end to end with chalked sketches

of geologic cross-sections of mountain ranges, showing faults, folds, and

overthrusts he's discovered during his wide travels among the world's mountains.

But of course his favorite outdoor laboratory was the North Cascades, where

he spent nearly 40 summers mapping the geology under grants from the GSA

(Geological Society of America), and there he encouraged many of his grad

students to find their theses areas. It was my privilege to join Peter as

his field assistant during the summer of 1950, and there I gained deep respect

for his binocular recognition of distant geologic structures and rock types,

and his rapid interpretation of the Big Picture, along with hammering and

packing out heavy loads of rock samples. The field studies always included

scrambling up the peaks and rest breaks for doing pencil sketches and watercolors

of views across the deep, glacier-cut valleys.

On Peter's 70th birthday, he received from Niki a thick notebook containing

entries from more than 80 of his graduate students. The love and respect

for the old professor came through with numerous anecdotes about his lectures,

geology field trips, wine-tasting sessions at the Misch home, and skiing

escapes from the classroom (which he encouraged among his grad students),

along with a sprinkling of limericks featuring their favorite "earthy

scientist."

Most students who didn't go on to grad school were unaware of Peter's

watercoloring talents. Most of his colorful and geologically detailed landscapes

were stacked in the basement, and those who visited the Misch home noted

only a few framed paintings on the walls--a couple Cascade peaks, a desert

sunset in Nevada, and a desert, lake, pagoda and wave-splashed coast of

China.

After Peter's passing, Niki allowed me to select my favorite--a view

of Mount Triumph done while we sat painting from a high meadow in the North

Cascades--now a treasured memento of a good friend and inspiring teacher.

Dee Molenaar, '50

Burley

Portrait of Professor Peter Misch courtesy Dee Molenaar.

|