Seattle native Peter Rice said good-bye to the city when he graduated from high school. He headed north to Alaska, where he worked at construction sites, on boats and in logging camps. But there came a time when he left the groves of Douglas fir for the groves of academe.

At age 26, he earned a degree in biology from the University of Alaska. Several professors encouraged him to stay in his adopted state and help others, so he continued on at the University of Alaska to complete his first year of medical school.

Alaska doesn't have a medical school in a bricks-and-mortar sense. But it does have something called WWAMI Spread out over one-quarter of the United States land mass, this program encompasses Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho and takes its name from the initials of the participating states--WWAMI (pronounced "whammy"). Its mission: joining forces with the University of Washington to educate medical students.

Basic science faculty at six state universities teach the first-year, UW faculty in Seattle teach the second year, and UW and community health professionals in towns throughout the region train future doctors at several stages, notably during the last two years of medical school.

In Rice's case, many professors he knew as an undergraduate were his first-year medical school teachers. With only 12 students in his class, Rice got individualized attention in anatomy and other subjects. For second-year courses in Seattle, his small class joined UW medical students from the other participating states, forming a medical school class of about 160.

"I took my third-year psychiatry clerkship, and obstetrics and gynecology clerkship in Anchorage," Rice recalls. He made rural health field trips to Bethel, a mostly Alaska Native village where the local doctors cover an area the size of Oregon, and also to Marshall, a village north of Bethel on the Yukon River.

"It was good exposure to see how health care was delivered in the bush," he says.

"All these experiences were part and parcel of what I felt was a welcoming, supportive atmosphere for doctors-in-training who wanted come back to Alaska," Rice says.

In 1988, when his residency in internal medicine at the University of Washington was over, one of his mentors invited him to practice in Ketchikan, a 17,000-person settlement in southeastern Alaska accessed only by boat or plane. Ketchikan is a place of seagoing splendor, but it could also be one of profound isolation if it weren't for the professional relationships the doctors and local hospital have with sister institutions elsewhere, including the University of Washington.

"While WWAMI is known for training rural physicians, a lot of people don't realize the amount of professional support the UW medical school continues to give to practicing health professionals in small medical communities like ours, or to much smaller ones with only one doctor," Rice says.

In June, Rice penned a commentary in the Ketchikan Daily News about his town's links with the UW--the availability via airlift of the trauma and burn centers at Seattle's Harborview Medical Center, a free phone line for physicians to consult with a UW specialist day or night, Internet access to patient data, and visits from UW medical faculty to Ketchikan.

In this age of for-profit hospital chains traded on Wall Street, Rice wrote, it's important for communities like Ketchikan to support public teaching institutions like the UW, and important for him to be affiliated with organizations that are values driven, not profit driven.

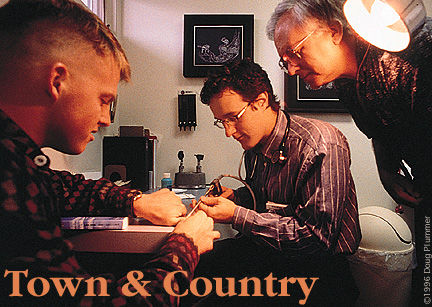

"Where My Patients Are My Friends"

Community Practice Training Once Considered a

"Heresy"

Research Also Part of WWAMI

Training Efforts

Send a letter to the editor at columns@u.washington.edu.