While Charles Odegaard made history as UW President from 1958 to 1973, alumni may not know that their president—a medieval historian—was a witness to history of much of the 20th century. In his autobiography, A Pilgrimage Through Universities, just released by UW Press, he recounts watching Adolf Hitler in a Nazi parade, dodging German submarines during convoy duty in the Atlantic, and even helping set the standards the Selective Service was using to draft military-aged men.

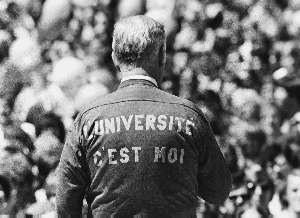

During his retirement party in "Red Square," Odegaard was given a sweatshirt with a phrase that roughly translates to "The Univeristy is me." Photo by James Sneddon.

Odegaard was born in 1911 in Chicago Heights, Ill. His paternal grandparents emigrated from Norway in 1880. The son of the president of a machine tools company, Odegaard grew up on the north side of Chicago. While neither parent had finished high school, they encouraged Odegaard's scholastic study and had an extensive library. In his autobiography, he says this family environment "preconditioned me for history as a discipline."

A brilliant student, Odegaard was co-valedictorian of his high school. He was also the beneficiary of 1920s-style "affirmative action." Dartmouth decided to expand its student base from mostly Eastern prep school graduates, and he was accepted into the exclusive college. He excelled as an undergraduate and was one of six senior fellows his last year. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1932 and won a Dartmouth fellowship to study medieval history at Harvard.

"I survived the second year as a graduate student at Harvard in the depths of the Depression with the least amount of money ever. I remember that I went many days without breakfast but had a 15-cent lunch consisting of a glass of milk and a sandwich from Hazen's [Restaurant] and a 35-cent special evening bargain at a cheap restaurant" he recalled in his autobiography.

He began his teaching career in 1937 at the University of Illinois, taking a leave of absence during World War II, where he served in the Navy and saw service in the North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Pacific theaters. "I was to have an intense exposure to men of very different skills and capacities, men from diverse and dangerous social origins and classes." He credits this "residue of knowledge about humankind" with aiding him in future roles as dean and university president.

Convoy duty in the North Atlantic was "among the days of greatest tension, most arduous and in a sense the most heroic of my war experience," he says.

After the war, he returned to Illinois but soon became executive director of the American Council of Learned Societies, a consortium of 24 disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. In that position, Odegaard helped draw up guidelines for student exemptions from the draft during the Korean War—exemptions that would still be in place during Vietnam. In 1952 he left the council for the University of Michigan, where he became dean of arts and sciences until leaving for Seattle six years later.

After his presidency, Odegaard floundered a bit before he found his bearings, his daughter recalls. Though he was a medieval historian, he took great interest in the intersection of science and the humanities, particularly medicine. He became a professor of higher education and biomedical history and wrote a book, Dear Doctor, on humanizing the practice of medicine.

The death of his wife, Betty, in 1980, was a blow, but Odegaard continued to serve on many civic and foundation boards and began writing his autobiography. In his later years, his memory suffered from a series of mild strokes. "My father never had Alzheimer's, as some people assumed," says Quarton. "He always knew his family. He just gradually began to forget names and got progressively worse."

"People have said to me, 'What a tragedy,' but I don't think so," she continues. "My father retained his social ability to the end. He was fairly peaceful about it. I don't think that he was unhappy at all."

Tom Griffin is editor of Columns.

|

Memorial gifts can be made to the Charles Odegaard Undergraduate Library or the Betty Odegaard Fund. Contact the Office of Development, University of Washington, Box 351210, Seattle, WA 98195-1210; phone 1-877-UW-GIFTS; |

- Return to March 2000 Table of Contents