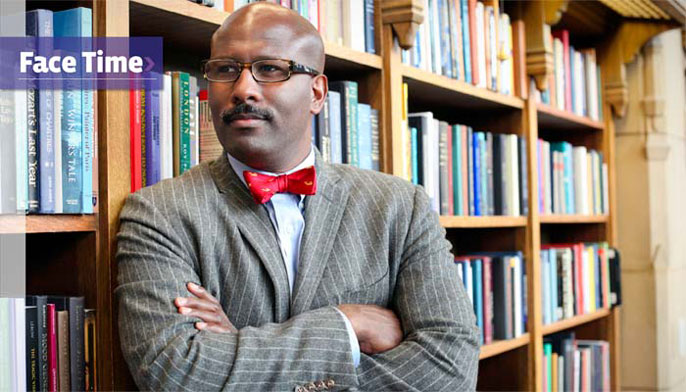

Who: Max Hunter, '02

Known as: Speaker, author and teaching fellow

Known for: Turning a street life into a scholarly life

When Max Hunter received his bachelor's degree from the University of Washington, The Seattle Times dubbed him the "most unlikely" grad in the class of 2002. That assessment was based on the winding journey Hunter took from the projects of San Diego to the classrooms of Seattle: one that included stints as a preppy hustler, a cocaine dealer, a drug addict, and a student in Japan. The transformation, however, was hardly simple or sudden; instead, it reflected for Hunter the complexity of the experience of many urban African-Americans. Pursuing a career in academia—first at Harvard and now as a UW Ph.D. student and teaching fellow at Seattle Pacific University—Hunter has, of late, begun sharing his story. He recently gave a talk in the Veterans of Intercommunal Violence series at UW's Clowes Center for the Study of Conflict and Dialogue, and is working on a pair of books.

Note: The version of the Max Hunter Q&A below is longer than the one that appears in the print edition of Columns.

Do you want people to use your story as a source of inspiration?

I'm more interested in challenging people to fulfill their potential; to get past their failures and accomplish something in life. I would like to inspire others to recover "linked fate," the idea that African-Americans see their personal fate as linked to the fate of the community. I'd also like to restore the prominence of literacy in the black experience. According to Toni Morrison, no other group of slaves has written as much as black slaves in North America. Literacy has been critical to black liberation and human formation.

What kind of feedback have you received since your talk at the Clowes Center?

I have received a flood of requests for dinner and lunch meetings, as well as invitations to talk or work with youth. One of my colleagues told me that as she was riding the bus on the way home, she heard some kids retelling my story to each other.

Has sharing your story made you more likely to step out of the classroom and into the community?

Having African-American professors visit my schools or local community centers meant a lot to me when I was a youth.

It helped me to imagine that people who looked and thought like me could find a space on campus to live, work and thrive.

I still get out to the community; however, my studies suffer for it. In my thinking, the entire city is the community. So, I will spend time with [local community organizer] Wyking Garrett and his youth; I might go to lunch or coffee with [Seattle City Council members] Tim Burgess or Sally Bagshaw; I might join fathers facing challenges at Marvin Charles' nonprofit [Divine Alternatives for Dads Services]; I could share my story in a religious setting or at Franklin High School; or I might spend time at the Seattle Art Museum trying to support Sandra Jackson-Dumont's work in the community.

What misconception about 'the gangster' would you most like to correct?

I'm interested in deconstructing the idea that kids who get involved in gangs or crimes are irrational or bestial. Many move on to do great things; in fact, the guy who first brought me into "the game" is now a scientist at a major American research institute.

I want to destroy binary thinking that allows us to abdicate our social responsibility to help youth who have made poor choices. I also would like us to think about how we determine whether someone deserves help based on their chronological age. Finally, I think that it's important to recognize that violence begets violence. On a daily basis, the media exposes youth to conflict as a tool for domination in our nation's domestic and foreign policy. Many kids also face violence in their communities on a daily basis. These realities shape both their worldview and their actions.

What are your plans after finishing the doctoral program?

I'd like to continue to teach and work in the community. I hope to do a master's degree in bioethics at the UW medical school. My dream, however, is to begin

a publishing company as a pedagogical tool for cultivating literacy and identities of competence. I want to recruit future authors from marginalized sectors of society and use reading, writing and

theory to help both youth and adults to develop an understanding of their own stories and develop a critical consciousness about their own lives and society.

How would you describe your teaching style? Is it more important for you to impart certain information or to imbue students with a certain approach to learning?

I like to think that I'm improvisational and relational. My teaching is student-centered because I want my students to develop leadership skills and take learning into their own hands. Subject matter is important, but I'm most interested in habits of mind, as well as my students developing reflexivity and identities of competence.

I think Paulo Freire's book Pedagogy of the Oppressed captures some of my underlying assumptions as to what a teacher's role is all about. I tend to see myself as a student among students, a partner with them in the world. But I like to have fun at the same time.

Please share a bit about the books you are working on.

One of my books is autobiographical. The other will focus on literacy in the African-American experience. I hope to demonstrate the enduring importance of reading and writing in the African-American experience for developing a sense of self, a critical consciousness and a counter-public sphere. Moreover, I want to make a link between black narratives from diverse regions and periods in history.

Whom do you most hope will read the autobiography?

Everyone, [especially] Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, Denzel Washington or Will Smith. I'd love to make a movie about

my story.

—Paul Fontana