|

UW Research into Learning Disabilities-Including New Teaching Tactics, Genetic Testing and Brain Imaging-May Finally Break Some Children's Roadblocks to Success. |

|

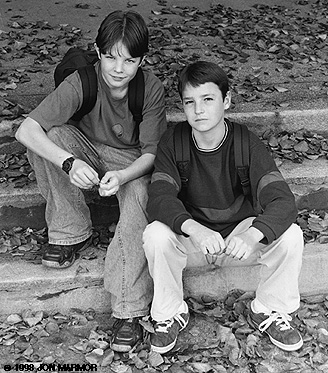

by Nancy Wick For Deborah Shipman and Debbie Daniels, the trouble came without warning. As the mothers of bright, verbal preschoolers, they never dreamed what was ahead. But in kindergarten, Kyle Shipman had difficulty recognizing the letters of the alphabet; in first grade Alex Matteson, Daniels' son, just couldn't seem to learn to read. Neither the mothers nor the boys' teachers knew what to do. Kyle and Alex were demonstrating the classic pattern of children with learning disabilities. They had seemed to develop normally—both physically and mentally—until they entered school. But when their reading skills failed to develop, their parents' world turned topsy-turvy. "I was devastated to find out that my wonderful, perfect child wasn't," Daniels remembers. "I was afraid for him. I wondered what this would mean for his life." Daniels' reaction is typical. Parents of children with learning disabilities are first surprised by a problem that comes out of the blue, then confused because they don't know what to do and finally frustrated that efforts to help their children often fail. The frustration builds when parents ask for help, but meet resistance. School officials told Kyle's mom they couldn't test him until second grade. Daniels ran into "tremendous resistance" when she asked that Alex be tested. "He's a boy and boys mature later," school officials argued. "Let's wait until third grade."

|

|

Dyslexic children use nearly five times the brain area as normal children while performing a simple language task, according to a new study by an interdisciplinary team of University of Washington researchers. The study shows for the first time that there are chemical differences in the brain function of dyslexic and non-dyslexic children. See UW news release. |

|

A novel treatment for dyslexia not only helps children to significantly improve their reading skills but also shows that the brain changes as dyslexics learn, according to a study by an interdisciplinary team of University of Washington scientists. See UW news release. |