After Pearl Harbor, as the U.S. Imprisoned Thousands of Its Own Citizens in Internment Camps, More than 400 Japanese American Students Had to Drop Out of the UW. This Is the Story of Some Forced to Leave—and the Efforts the UW Made to Protect Them.

On a quiet day in late June 1942, a few weeks after the UW’s commencement ceremony, a University of Washington dean slipped out of his office, got into his car and started to drive to Puyallup.

He had an important duty to perform, but this appointment was not recorded in official University records, nor can any account be found in local newspapers of that era. The dean may have wanted to keep his trip a secret. If word got out, there could be angry letters, raging editorials and perhaps a phone call from legislators in Olympia.

On the seat next to him was a stack of UW diplomas. Though there was a war going on and the campus would soon be packed with men—and some women—training for the military, the University of Washington had just lost more than 400 students. This official was on a trip to make a symbolic gesture to some of them.

The destination was the Western Washington Fairgrounds in Puyallup, but there were no amusement rides or animal husbandry exhibits that summer. Underneath the grandstands and in the stables that once housed cattle, thousands of local Japanese American families were gathered in an "assembly center called Camp Harmony. Under Executive Order 9066 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the military had ordered more than 110,000 Japanese Americans to leave their homes on the West Coast—including 70,000 who were U.S. citizens.

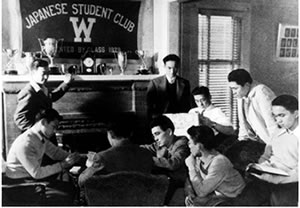

For most of the UW students who were Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans), the order to leave came in May, before the end of spring quarter. Despite pleas from President Lee Paul Sieg and Arts and Sciences Assistant Dean Robert O’Brien, the Army refused to let Nisei students finish their studies before being sent to the camp. They had three or four day’s notice and then they were gone. Army officials demanded that Japanese American faculty also leave—even though most faculty members were American citizens (one was a veteran of World War I). Even faculty teaching Japanese language courses—crucial to the war effort—had to leave.

Because of the internment orders, the June ceremony at Camp Harmony lacked any of the pomp and circumstance traditionally found at a college commencement. There wasn’t much of a crowd either. The camp officials wanted to limit the audience, perhaps for security reasons. "All those who have graduated in the past fall or spring quarters will be allowed to attend, the Army declared in a memo to the camp inmates. "All those of senior standing at the University of Washington will also be able to attend. Each graduate will be allowed to invite their immediate relatives and/or friends, approximately four each.

"It was not a dress-up occasion, recalls George Mukasa, ’42, one of the UW graduates who received his diploma that day. "I was there with a T-shirt on. The economics major was the first member of his family to graduate from college, yet he can’t remember if his mother or three siblings were present.

Mukasa is fairly certain that Business and Economics Dean Howard Preston gave him the diploma. "They called my name and handed over my diploma and a graduation packet. It was very simple. Other UW officials may have also attended the event. Letters in the UW archives suggest that Arts and Sciences Dean Edward Lauer and Registrar Irvin Hoff were there.

"I thought it was pretty nice. They didn’t completely ignore us, recalls Mukasa. At the same time, he says the ceremony was "pretty anti-climactic. There were so many other events over the past seven months—starting on Dec. 7—that seemed more significant.

There is no record of any other college or university commencement ceremony at Camp Harmony. The UW was probably taking a public relations risk by holding even a simple event. But this gesture is symbolic of the University’s reaction to the idea of imprisoning Japanese Americans in the months after Pearl Harbor.

Before the decision was final, several UW officials testified against the proposal to send American citizens to internment camps. They then argued that their students and faculty should be exempt from the order. When that failed, they tried to find places at other universities for students willing to transfer—and got 58 out before they had to report to the camps. Student voices also opposed the internment. Editorials in the Daily defended Japanese American students and two UW undergraduates testified at a Congressional hearing against the idea.

These voices of reason were drowned out by racism and war hysteria, says American Ethnic Studies Professor Tetsuden Kashima. After Pearl Harbor, military and government officials feared a Japanese attack of the West Coast. They considered the Japanese American population a hotbed of sabotage and espionage.

"The Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted, wrote Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, the military official who ordered the internments. He added that there was "no ground for assuming that any Japanese, barred from assimilation by convention as he is, though born and raised in the United States, will not turn against this nation, when the final test of loyalty comes.

Powerful media voices—including columnists Walter Winchell and Walter Lippmann—advocated internment. In addition, says Kashima, there was a failure of political leadership. Attorney General Francis Biddle and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover told President Roosevelt there was no need for the imprisonment of American citizens. "Even the Office of Naval Intelligence opposed the internments, Kashima says. But Roosevelt wasn’t listening.

Go To: Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5

Stolen Years - Part One: Reader Comments